Sepsis

Sepsis is common and often deadly. It remains the primary cause of death from infection, despite advances in modern medicine like vaccines, antibiotics, and intensive care.

What is Sepsis?

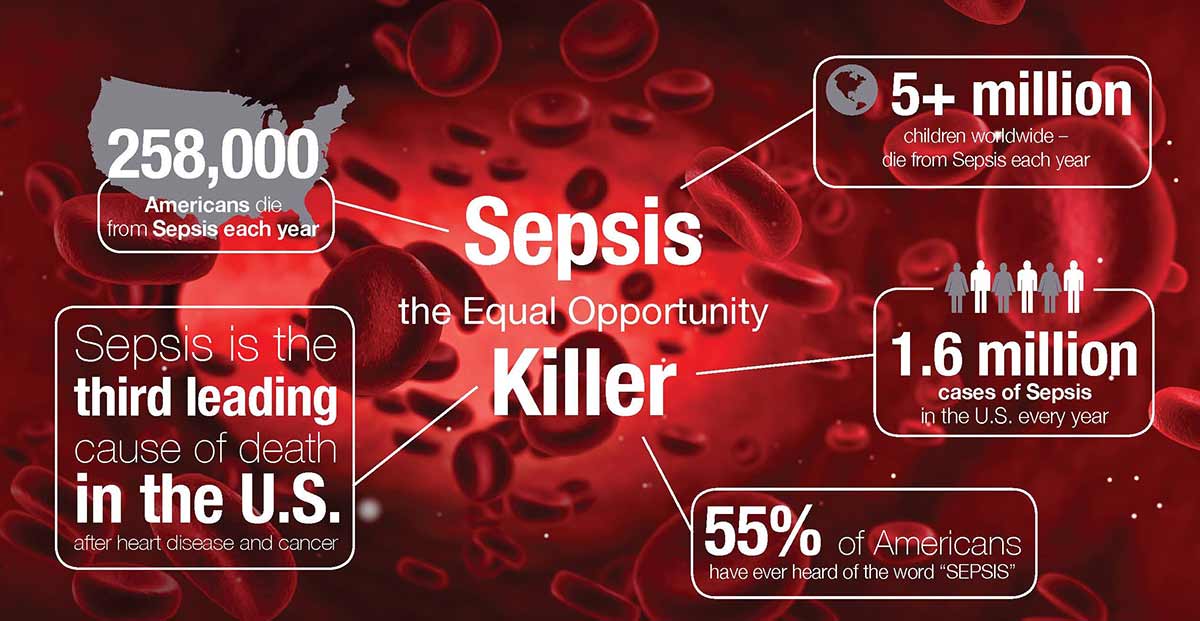

Sepsis is a global healthcare problem. It is more common than heart attack, and claims more lives than any cancer, yet even in the most developed countries fewer than half of the adult population have heard of it. In the least developed countries, sepsis remains a leading cause of death.

It is known as “blood poisoning”, sepsis is a life threatening medical condition that arises when the body’s attempt to fight an infection results in the immune system damaging tissues and organs. This chaotic response, designed to protect us, causes widespread inflammation, leaky blood vessels, and abnormal blood clotting resulting in organ damage. In severe cases, blood pressure drops, multiple organ failures ensue, and the patient can die rapidly from septic shock. Patients vary in their response; the severity of their sepsis and the speed with which it progresses is affected by their genetic characteristics and the presence of coexisting illnesses, as well as the numbers and virulence of the infecting micro-organism. Some patients seem not to deteriorate until late in their illness, in others sepsis progresses rapidly and can be fatal within a few hours.

What can be done about Sepsis?

Cost-effective basic interventions save lives. The best centers, mainly in industrialized countries, have doubled patients’ chances of survival, simply by recognizing the condition and responding rapidly. However, only 10-30% of patients with sepsis receive excellent care. Saving lives depends not just on treatments specific to a particular infection, but rather a focus on early recognition and awareness of sepsis, rapid antimicrobial therapy and resuscitation, and vital organ support. In short, sepsis is a medical emergency and each hour matters. A better understanding of sepsis as the final common pathway of illness due to infection is essential to drive improvement. This applies to the medical profession, governments and the general public. Furthermore, some infections that could lead to sepsis can be prevented through vaccination for diseases like influenza, pneumococcus and meningitis and also strategies to prevent healthcare-associated infections are effective to reduce the burden of sepsis.

What causes Sepsis?

Sepsis is always triggered by an infection. Sepsis occurs as a result of infections acquired both in the community and in hospitals and other health care facilities. The majority of cases are caused by infections we all know about: pneumonia, urinary tract infections, skin infections like cellulitis and infections in the abdomen (such as appendicitis). Invasive medical procedures like the insertion of a catheter into a blood vessel can also introduce bacteria into the blood and trigger sepsis. Normally, when we suffer a minor cut, the area around the injury swells and becomes hot and red. This is the immune system in action. To fight any infection and to form a blood clot to stop bleeding, the body must get white blood cells and platelets into the tissues surrounding the cut. The body does this through inflammation, which is managed by the immune system. The blood vessels swell to allow more blood to flow, become leaky so that the infection-fighting cells and clotting factors can get out of the blood vessels and into the tissues where they’re needed, and we see the typical hot, red swelling.

Sepsis is best thought of as this process in overdrive: inflammation is no longer localized to the “cut”, but is now widespread affecting all of the body’s organs and tissues. The body’s defense and immune system go into overdrive, leading to widespread inflammation, poor perfusion, organ failure and septic shock. Most types of microbes can cause sepsis, including bacteria, fungi, viruses and parasites such as those causing malaria. Bacteria are by far the most common culprit, but it is important to understand that viral infections with seasonal influenza viruses, the Dengue and Ebola viruses may also progress to acute organ dysfunction and result in death from multiple organ failure and septic shock.

Sepsis is the final common pathway in the vast majority of deaths from infection worldwide.

Who gets Sepsis?

Sepsis does not discriminate. It affects all age groups and is not respectful of lifestyle choices. Vulnerable groups such as new born babies, small children and the elderly are most at risk, as are those with chronic disease and weakened immune systems. It is not a disease confined to healthcare settings, though most patients with established sepsis will be cared for in hospital. Age, sex, and race or ethnic group can all influence the incidence of severe sepsis, which is higher in infants and elderly persons than in other age groups, higher in males than in females, and higher in blacks than in whites . People with chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, cancer, AIDS, kidney or liver disease, are also at increased risk, as are pregnant women and those who have experienced a severe burn or physical injury.

World Sepsis Day September 17th.

Symptoms

Many doctors view sepsis as a three-stage syndrome, starting with sepsis and progressing through severe sepsis to septic shock. The goal is to treat sepsis during its early stage, before it becomes more dangerous.

Sepsis

To be diagnosed with sepsis, you must exhibit at least two of the following symptoms, plus a probable or confirmed infection:

Body temperature above 101 F (38.3 C) or below 96.8 F (36 C)

Heart rate higher than 90 beats a minute

Respiratory rate higher than 20 breaths a minute

Severe sepsis

Your diagnosis will be upgraded to severe sepsis if you also exhibit at least one of the following signs and symptoms, which indicate an organ may be failing:

- Significantly decreased urine output

- Abrupt change in mental status

- Decrease in platelet count

- Difficulty breathing

- Abnormal heart pumping function

- Abdominal pain

Septic shock

To be diagnosed with septic shock, you must have the signs and symptoms of severe sepsis — plus extremely low blood pressure that doesn’t adequately respond to simple fluid replacement.

When to see a doctor

Most often sepsis occurs in people who are hospitalized. People in the intensive care unit are especially vulnerable to developing infections, which can then lead to sepsis. If you get an infection or if you develop signs and symptoms of sepsis after surgery, hospitalization or an infection, seek medical care immediately.

Causes

While any type of infection — bacterial, viral or fungal — can lead to sepsis, the most likely varieties include:

- PneumoniaAbdominal infection

- Kidney infection

- Bloodstream infection (bacteremia)

The incidence of sepsis appears to be increasing in the United States. The causes of this increase may include:

- Aging population. Americans are living longer, which is swelling the ranks of the highest risk age group — people older than 65.

- Drug-resistant bacteria. Many types of bacteria can resist the effects of antibiotics that once killed them. These antibiotic-resistant bacteria are often the root cause of the infections that trigger sepsis.

- Weakened immune systems. More Americans are living with weakened immune systems, caused by HIV, cancer treatments or transplant drugs.

Risk factors

Sepsis is more common and more dangerous if you:

- Are very young or very old

- Have a compromised immune system

- Are already very sick, often in a hospital’s intensive care unit

- Have wounds or injuries, such as burns

- Have invasive devices, such as intravenous catheters or breathing tubes

Complications

Sepsis ranges from less to more severe. As sepsis worsens, blood flow to vital organs, such as your brain, heart and kidneys, becomes impaired. Sepsis can also cause blood clots to form in your organs and in your arms, legs, fingers and toes — leading to varying degrees of organ failure and tissue death (gangrene).

Most people recover from mild sepsis, but the mortality rate for septic shock is nearly 50 percent. Also, an episode of severe sepsis may place you at higher risk of future infections.